This article is expanded from an answer to that question on Quora.

A quick story.

I was teaching Art History and we were”dissecting” a painting in discussion.

A fellow in the back said, “I don’t see any of what you are all talking about.”

So I asked him, “What do you see?”

This was his reply, “It doesn’t matter because I’m color blind.”

That put a stop sign on the discussion.

My mouth got ahead of my brain, “Let’s trade places, “J”.

You describe what you see, and I’ll take notes,”

We physically changed places.

I’ve never seen that painting the same since and I applauded the student for his courage.

Sometimes, when working out an image I think about what it might look like to “J”.

It’s one thing to say everyone sees something different.

It’s quite another thing to have to confront that reality front and center. Color-blindness is physical deformity that points to the general reality of “How do we see?”

Most of us have two functional eyes separated by a nose. Light enters each eye. The light is transformed into neural energy and delivered to the brain.

Two separate images go to two separate sites in the brain. At some point, a single image is composited from the two separate images and interpreted by the sum total of our visual experiences.

Our brains seek out patterns and quickly match the “new unknown” to what is already “known”.

This is not as technical as it is how we humans operate. Our particular stories are the result.

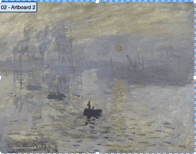

Claude Monet made a painting called “Impression- Sunrise”

It’s ubiquitous enough that the mere title for many will recollect the image. I’m including it below.

(with no filter applied)

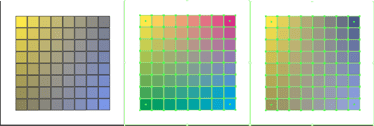

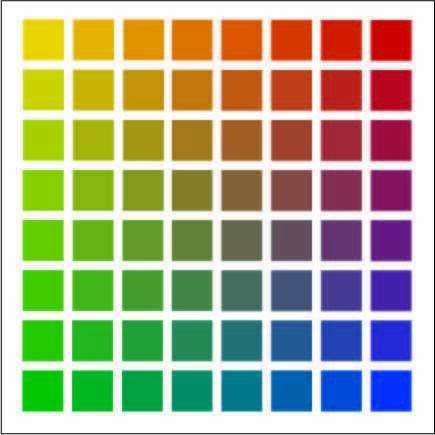

The stunning image is how the effect of the “sun” is accomplished. Books have been written on this. The assunmption is, the viewer has two normally functioning eyes. Monet was careful to get just the right red-orange and bnlue purple to create the inevitable vibration that occurs. But what does “J” from the story above see?

(with colorblind red filter applied)

The digital filter I used is an algorithm based on the study of color-blindness.

This is why I am a staunch proponent of “the conversation” between the viewers and a work of art. Some artists might argue for a visual image to be “self-explanatory”, that requires us to set aside our own experience for those of the artist-maker that are not our own. This ultimately undermines the connections we viewers might gain from experiencing the art image. I need to add, that in many cases the differences might be small, but keep in mind “J”‘s issue.

Did you notice that previous recollected experiences influence the image we think we see?

This is where the sharing of vision is most important, and where the story of the painting takes root.

Yes, it starts with the artist pushing materials around as (s)he chases after the mind’s eye image. That is only the beginning.

Even as the artist works, (s)he is both maker and viewer. How else are the brushstrokes laid in?

Once the artist walks away, the material residue is left for all to see, and understand.

The artist’s story is but one narrative.

The work becomes more complete with the cloud of viewers. The richness lies with the collection of stories created by the seeing.

The responsibility of the artist, it seems, is to give the viewer something compelling to see.

That compulsion need not necessarily be narrative nor referential. It does however need to be arresting in the sense of stopping us from our daily progress. The image begs us to spend some time with it.

It is time well spent for the individual, for the art, for the artist, and for our general societal well-being.

It’s just a thought.

As always, share a thought or comment with me. Share the article with your friends. Thank you for taking minute on the Front Porch.

Keep up-to-date

Receive new posts automatically in your inbox. We will never share your email address or personal information for any reason.

I really enjoyed this, Steve!! I’ve always loved art of all types, but never thought about seeing it through the eyes of a color-blind person.